Someone said: “The problem with punctuality is that there is nobody there to appreciate it.” Similarly, the problem with control-room ergonomics in the South African context is that it has been largely nonexistent. Maintaining sound ergonomic or human factor principles has become essential as the evidence, that continues surfacing, indicates that workplace designs taking human factor principles into account have been less likely to lead to errors and accidents and more likely to improve operator efficiency.

The symptoms of ergonomically-neglected control-room designs accumulate until they eventually snowball by:

* Causing more unforced operator errors which could have been prevented.

* Leading to longer reaction times required by the operator to decode, decide and act on information received.

* Resulting in reduced operator efficiency.

* Which reduces the operators' self confidence and job satisfaction.

* Ultimately causing avoidable loss of production.

* Finally causing everyone to be losing something.

Who is to blame? is a question always repeated in cases of events during which the operating staff either interfered or failed to interfere. The search for the cause of such events normally focuses on the human-machine interface. The most significant changes to recent control-room designs have been the introduction of distributed (digital) control systems. This resulted in a completely changed human-machine interface (HMI), as operators are now receiving virtually all their information from or via one or more computer displays, and control the plant by using some type of computer input device. In addition, a common denominator of the modern computer-based technologies is the order-of-magnitude increase in the amount of information available to the operator. Naturally, human factor considerations have expanded substantially since the days of 'knobs and dials'.

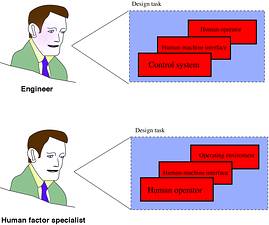

When designing a new control-room, both I&C engineers and human factor specialists should assist in the design because of the differences in their priorities. The engineers want to get the control system and the HMI absolutely right, while the human factor specialists seek to change the things that the operators use as well as the environment to better match (and adapt to) their capabilities, limitations and needs. Figure 1 illustrates this mismatch in priorities. To identify the mismatch in terms of the prioritised position of the operator is obvious. However, managing this mismatch to the benefit of the HMI design presents its own problems and challenges. The reason for this is that engineers, with their educational roots in the exact physical sciences, have to some extent always found it difficult to understand human factors. On the other hand, behavioural scientists such as human factor specialists seldom have the necessary engineering or process background to fully comprehend complex industrial processes and the industrial practices driving and supporting its design.

Today's control-room designer can no longer view the design task as a simple 'packaging' problem; the designer has to incorporate principles from a diverse array of technologies and disciplines. Therefore, most international utilities employ multidisciplinary teams to do their control room designs. The participants, as a minimum should include the project owner/project management, the I&C engineer, an ergonomist, some end users/operators, maintenance staff and an interior designer. Human-machine specialists support this, as a human-machine system is not only a technical system but also a very complex organisational and social system, where automation is only a component of the overall system.

Engineering considerations

Process control can accurately be described as a human-machine system, highly influenced by scientific and technological advances. When new computer-based technology is implemented in old as well as new plants, it inevitably changes the allocation of functions between the human and the machine as well as composition of this interface. Process control tasks can hence be performed exclusively by the machine, or exclusively by the human, or by both via the mentioned interface.

I&C engineers have a tendency to look upon the operator functions simply as 'rest-functions', which are not suited for automation. The role of the operator seems seldom to have been designed with any degree of precision; he or she simply does everything that remains to be done to work the plant, after the designers have made their decisions. Modern I&C systems leave the designers with loads of freedom and the trend is to leave more and more to the system and less and less to the operator. The situation is then that several tasks are taken out of the hands of the operator, who thus loses touch of the plant at the same time as the increasing complexity of the plants demand more knowledge of the functions and reactions of the plant. The present-day I&C engineers' answer to this is to build the required expertise into the software of the control system, isolating the operator even further. It appears that I&C engineers apply the computing ability of process computers and scada systems almost exclusively to the benefit of the control system, without always appreciating the importance of a totally informed operator.

Ergonomic considerations

Professional control-rooms incorporate principles established in the fields of anthropometry, physiology and perceptual psychology. Creating an ergonomically ideal workplace means that the designer must consider the following factors when deciding on dimensions, angles and layouts:

* Physical aspects such as a person's size and reach, line of sight.

* Cognitive factors such as attention, decision-making, memory and perceptivity.

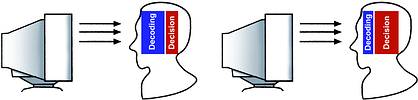

Recognition, assessment and decision-making (Figure 2) on the basis of experience plus an in-depth knowledge of the process are the cognitive tasks that control-room personnel have to perform. Good designs assists in these activities, helps to prevent errors, and accommodate the significance of laws of perception such as:

* The eyes receive about 80% of the information a person assimilates. This is why the visual presentation of information plays such a major role in control-rooms.

* Humans in general experience conscious perception (that is by deliberately concentrating on something) and subconscious perception (that is information is received involuntarily).

* The more the design promotes subconscious perception processes, the more it relieves the operators' burden, thus enhancing their capacity for mental activity.

General design considerations

Automated plants are without exception major investments - they incorporate expensive technology and feature high-performance equipment. Despite being highly automated, it is still the human operator who takes the ultimate responsibility. So it is worthwhile ensuring close-to-perfect control-room surroundings. After all, the operators have an important job to do, and a high level of productivity and operating reliability can only be achieved if they do it properly. Operators should not get tired, even if nothing happens for hours. If the need arises, they must be able to make the correct decision at very short notice and must take appropriate action. They must always have an overview of the entire plant, without losing sight of important details.

Operators often describe their task as watching a most impressive movie (when they first enter into the control-room), without any significant scene changes thereafter. The designer's challenge is to keep them awake, alert, assertive and interested in this 'boring movie'.

Conclusion

To be able to concentrate on their work for long hours, control-room operators need:

* To be motivated.

* To identify with their work.

* To experience personal well-being,

* To feel safe.

* To have a sense of self-worth.

This is exactly the aim of advocating the need for ergonomic input into any control-room design: to provide just such a working environment; to take human needs into account and create a pleasant atmosphere in which people will enjoy working for a long time.

I&C practitioners in general acknowledge this, but unfortunately present engineering studies fails to train and direct them on how to adjust their designs to accommodate these areas.

EEU Consulting

(011) 393 3120

© Technews Publishing (Pty) Ltd | All Rights Reserved