The objective of an alarm system is to minimise or prevent physical and economic loss through operator

intervention.

Keywords: [Alarm management, bad actor, benefit, best practice, case study, champion, compliance, continuous, decision making, disaster, economic, EEMUA 191, flooding, guideline, ignore, incident, ISA, KPI, liability, loss, mass acknowledgement, motivation, nuisance alarm, overload, performance, quality, regulatory, risk, safety, strategy, trip]

Abstract

In this paper Dave Wibberly looks at some of the motivators and best practices for alarm systems and then discusses the conflict between the published KPIs, which are regarded as those required to meet best practice vs. practical means to achieve these metrics. Through two case studies he highlights some of the difficulties plant operators may face and the possible outcomes when they embark on implementing an alarm strategy.

Introduction

The ultimate objective of an alarm system is to prevent, or at least minimise, physical and economic loss through operator intervention in response to the condition that was alarmed on any given process.

Alarm management has taken on new meaning since being identified as one of the key protagonists in major process plant disasters of recent years, such as BP Texas City, Bhopal and 3 Mile Island.

Spurred on by the findings of enquiries into these disasters some very interesting work has been done by the large process companies, vendors and industry organisations like the Electrical Equipment Manufacturers and Users Association (EEMUA) and the Instrumentation Society of America (ISA).

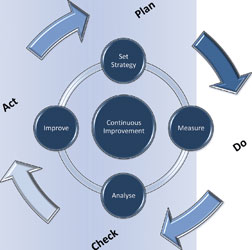

By firstly recognising the problem; accepting the need for an alarm management strategy; and applying technology to the process, companies can achieve multiple benefits. These include a more motivated and focused staff, clearly identified efficiencies and improved profitability while minimising the potential liability of management.

Why change anything?

Strategic motivators can be classified as forced or voluntary. Forced motivators may be compliance (or regulatory) or they may relate to risk mitigation. Voluntary motivators are those which are driven by perceived business benefits.

The adoption of an alarm management strategy may be driven by both forced and voluntary motivators.

What is an alarm?

The generally accepted definition of an alarm is:

'An alarm is an event to which an operator must react, respond and acknowledge.'

Therefore the purpose of an alarm system is to alert an operator(s) to a potential problem, that if not addressed will cause some production, process, quality or safety compromise. To put an economic slant on this: the alarm system is there to prevent, or at least minimise, physical and economic loss through operator intervention.

Current problems

Studies have shown that there are several common problems experienced in alarm systems:

* There are too many nuisance alarms.

* Alarms are ignored by operators.

* Alarm viewers are underutilised.

* Operators perform mass alarm acknowledgments.

* The systems fail to provide real insight to support operator decision making.

These problems lead to undesirable consequences. Operators presented with too many alarms may overlook an important indicator of an abnormal situation, or be so overwhelmed that they choose to unnecessarily trip the unit as a safety measure instead of trying to interpret the information being conveyed.

Both of these scenarios can significantly impact the safety of plant personnel and the efficiency of plant operations. At the same time risk is increased. There is a higher chance of some catastrophic failure occurring, leading to massive liability issues, as happened in incidents like BP Texas City, Bhopal and 3 Mile Island. Less catastrophic but still significant are the risks associated with consequent reduced production, quality issues and poor staff motivation.

Nuisance alarms

Most scada installations are configured to create an over-abundance of alarms. Cited here is a large diamond mine customer who after the project was delivered had over 10 000 alarms configured. This is information overload for operators. According to the EEMUA 191 guidelines, an alarm is classified as an event to which an operator must react, respond and acknowledge (not simply acknowledge and ignore) and no plant should have more than six such alarm occurrences an hour.

Alarms are ignored

Many alarms are simply ignored by operators because so many are either inconsequential and/or irritating. Where the operator is overwhelmed by trivial information (s)he may miss or ignore genuine alarms.

Alarm viewers are underutilized

Most process faults are adequately displayed by graphical components on the mimic and these are used as a starting point to initiate the correction process making a ‘noisy’ alarm viewer redundant when it should be the most important global view of any process indicating the current health of the process.

Continued on the web

For the complete article visit www.instrumentation.co.za/+C9204

For more information contact Dave Wibberley, Adroit Technologies, +27 (0)11 658 8100, [email protected], www.adroit.co.za

| Tel: | +27 11 658 8100 |

| Email: | [email protected] |

| www: | www.adroit.co.za |

| Articles: | More information and articles about Adroit Technologies |

© Technews Publishing (Pty) Ltd | All Rights Reserved