In the previous article of this series (Part 2) we looked at optimising control by reducing the scheduled bus traffic, which reduced the macro cycle. We looked at the manner in which Foundation Fieldbus allows the ad hoc creation of function blocks, and the flexibility to decide where the control is to reside. The second half of Part 2 ran through some ‘what if’ scenarios, and discussed the way that a Foundation Fieldbus installation would respond to various upsets and disasters. Advantages of distributed control were highlighted. The story continues...

Although it might sometimes be a case of preference, control in the field usually makes sense when there are economical or technical benefits to the user. When comparing the cost of Foundation Fieldbus to other systems, every control block used in a field device replaces an analog channel on a DCS. Within a Foundation Fieldbus system itself, however, there is no obvious economic benefit from running the control blocks in the devices, unless the controller is limited in the number of blocks or links it can handle, a high degree of loop integrity is required - or the controller is not necessary at all.

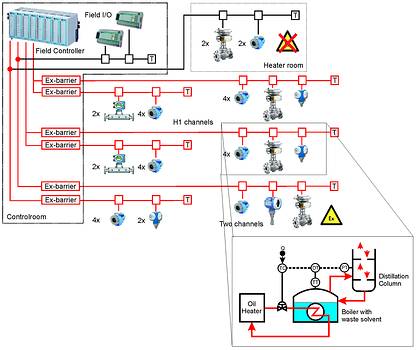

As discussed previously, where blocks are running, control in the field does have an effect on the macrocycle length. By careful design of both segment and control strategy, most applications can be effectively solved. Limitations are set by the number and type of blocks available and the number of links that can be supported. These in turn depend on the field device and host system. The examples that follow indicate what control in the field looks like in practice, see Figure 1. The host and devices used supported multivariable optimisation.

Simple feedback flow control

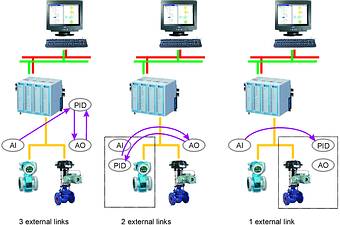

The optimal location for the PID block of a control valve is the positioner itself, see Figure 2. Not only does this reduce the number of links and loop integrity, it also ensures that the block assumes fail-safe mode when the input is bad. There is no intervention by operator or other devices in the network.

Temperature control in a distillation column

As a continuous process, the regulation of temperature in distillation columns (or boilers) provides an ideal application for control in the field. In the application shown (see Figure 1) solvents were distilled in batches, meaning that there had also to be some kind of ramp control over the initial boiler heating phase. This was done by means of a characteriser and arithmetic block, which together with a constant block for tracking, were run in the valve positioner. In all, five external publisher links were required. Had the application been implemented in the controller more than twice as many links would have been required, making a noticeable impact on macrocycle time and decreasing the degree of loop integrity. When many loops are necessary, the reduction in cost becomes more apparent because it is not necessary to replicate local controllers that execute each temperature control loop independently.

Motor control from a field I/O device

As mentioned earlier, currently Foundation Fieldbus is not very strong in logical control. The general method of managing analog and digital I/O signals is to add I/O cards to the controller. There are different options: to integrate PLC platforms into Foundation Fieldbus or to use FF field I/O devices. The latter, mounted locally on the H1 segment, was the solution selected. By using a flexible function block, a small degree of logical control is available in the field. This was ideal for the motor control centre in the distillation plant just described.

Simple is beautiful

Does Control in the Field have a future? As control systems have increased in size and capabilities, the remoteness and complexity generated by a proliferation of smaller, faster and cheaper technological components in a large system has been forgotten. Could this be one of the main reasons why people are 'afraid'? Is it the thought of relying on thousands of components to work together reliably - components that no longer deliver information to one source, but which, in order to control a process, distribute it, apparently without supervision, across the field?

From the technical point of view, there is no longer a need for a centralised control room. "(Today's) control systems are advanced enough that the control room is not needed to co-ordinate the control". Perhaps the way ahead is to go back to the field and create small, manageable units, capable of operating by themselves, but reporting regularly to the supervisory system. Foundation Fieldbus is ideal for such systems, since a segment can also be operated without a 'controller', indeed without control, when required.

At the same time there is a need for 'simplicity'. Simplicity does not preclude users from undertaking skilled tasks such as connecting up the equipment, rather it implies that they would like to see a lot more plug and play in device integration, configuration and design of the control strategy.

Undeniably, Fieldbus is an 'enabling' technology, but let us not forget the people who must work with it. Manufacturers can make fieldbus reality much simpler and more effective. As result, fears and concerns will no longer find the nourishment to sustain them. When the Zombies (from Part 2, in the March 2003 issue) can be exchanged and put to rest at the push of a button, and the plant manager can sleep well at night, the goal will have been reached.

For more information contact Grant Joyce, Endress + Hauser, 011 262 8000, [email protected]

This serialised paper was printed with permission of the Fieldbus Foundation, the copyright holder.

| Tel: | +27 11 262 8000 |

| Email: | [email protected] |

| www: | www.endress.com |

| Articles: | More information and articles about Endress+Hauser South Africa |

© Technews Publishing (Pty) Ltd | All Rights Reserved